https://ocula.com/magazine/conversations/archie-moore/

A conversation with Archie Moore

Image: Archie Moore.

Archie Moore’s practice draws attention to the cultural and social assumptions on which contemporary Australian society is built. For the 20th Biennale of Sydney, Moore compares multiple histories on a site originally known as Tubowgulle, on Gadigal land and now commonly referred to as Bennelong Point. At this location, Moore has built Bennelong’s Hut, a replica of the structure that Governor Arthur Phillip built in 1790 for Woollarawarre Bennelong, a member of the Wangal clan and a central figure in Sydney’s early colonial history.

Congratulations on your participation within the 20th Biennale of Sydney: The Future Is Already Here—It Is Just Not Evenly Distributed, can you tell us more about the work you will be showing at the biennale?

I am working with Kevin O’Brien, an indigenous architect, and builders to reconstruct Bennelong’s Hut in approximate location of the original structure. It will be located in the Royal Botanical Gardens opposite the Sydney Opera House. This was a gift from Captain Philip upon request from Bennelong and importantly, it is the first residential building built for an indigenous Australian by a white person. It is 12 square meters, made of bricks with a tiled roof. One door, a window and a chimney. Whilst it will resemble what we know of Bennelong’s Hut on the outside it will resemble what I remember of my grandmother’s hut on the inside, both were dirt floor huts. It is intended to be a meditative space to sit inside, look out the front door to the opulence of the Opera House and perhaps ponder who has benefited from resource-rich Australia over it’s occupied history. It is called A Home Away From Home (Bennelong/Vera’s Hut).

Image: Archie Moore, A Home Away From Home (Bennelong/Vera’s Hut), site visit. Courtey The Commercial, Sydney.

This sounds like a process to both highlight and problematise collective histories in Australia. Could you tell us more about your research process for this new work, and how you originally became interested in Bennelong’s story?

The curatorial idea of embassies for the 20th Biennale of Sydney made me think about Bennelong and his hut. This hut being the official residence of a diplomat, which is what Bennelong was then considered, and the idea of an embassy as being a sovereign state on foreign soil. Bennelong was living outside his country, which provides another complicating layer to his story but he engaged with Captain Philip in a diplomatic way conveying information between two worlds. Bennelong would also be invited to Government House for social occasions, here performing the diplomatic role.

Yes, Bennelong’s story provides a curious case study in Australian diplomacy at the time. As you highlight his hut ironically functioned as a gifted diplomatic lodge posed on ‘foreign’ colonial ground, despite Bennelong’s obvious connection to the land as a traditional custodian. Earlier you mentioned an aesthetic connection in your work, which draws a relationship between Bennelong’s story and your own grandmother’s history; can you tell us more about this?

My grandmother lived in a hut in Glenmorgan, Queensland. It had a dirt floor like Bennelong’s. I was thinking about the inequality of distribution of wealth—if there were any distribution at all—and which is why my grandparents were living in corrugated huts when the rest of the town had houses. Aboriginal people should be the richest in the country, but where has all the money generated from this land’s resources gone? Why are there problems with indigenous health and living standards when the state only has to allocate care to 3% of the population?

In addition to these ideas of equality, I’m also interested in memory and memory of a site, the idea of trans-generational inheritance of trauma, phobias, anxieties, desire etc. or a person’s or a people’s psychological make-up can be affected by events in a previous generation’s which have been relayed through genetic memory. I have an experience when I see a particular clearing, a pile of rocks or some other natural feature when I’m out West. Like an attempt at communication from the land but the techniques to decipher this have never been passed onto me. The Opera House appears to mimic a few shells on top of one of the middens that existed at Bennelong’s Point in the distant past.

Image: Installation view, Archie Moore, Blood Fraction, 2015. One hundred individually framed pigment UltraChrome ink prints on Epson Archival Matte Paper, overall installed dimensions 325 x 275 x 3.4 cm. Courtesy The Commercial, Sydney.

You have worked collaboratively a few times in the past; I’m thinking of your collaboration with the perfumer for Les Eaux d’Amoore, for your exhibition at The Commercial Gallery in Sydney in 2014. Now for the biennale, you will be collaborating with leading indigenous architect Kevin O’Brien. Can you tell us more about what you learn through working in a collaborative context?

There are no archival plans of Bennelong’s Hut in existence; the only information available is a description of measurements and materials. It is depicted in a few drawings and paintings from a great distance, across the cove, without detail. Kevin is familiar with this type of colonial structure and says it was quite common during this time. I learnt a bit more about this type of vernacular architecture and it’s materiality, for example the type of brick and orientation of window, door and chimney to each other and to natural elements as wind and arc of setting/rising sun. I wanted to work with Kevin because I needed the structure to stand up and stay put but also wanted to work with another Indigenous person for this project.—[O]

——

—-

—-

—-

—-

—-

Artlink » vol 35 no 2 | June 2015 » Archie Moore – 14 Queensland Nations: (Nations imagined by RH Matthews)

Frances Wyld, review

Archie Moore – 14 Queensland Nations: (Nations imagined by RH Matthews)

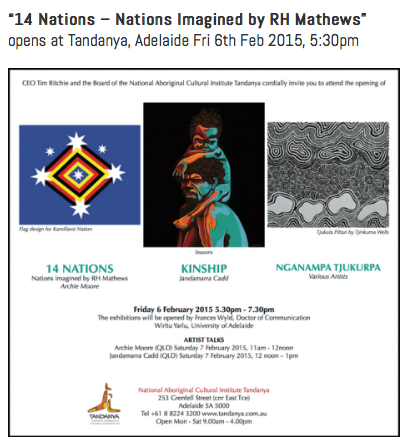

Tandanya National Aboriginal Cultural Institute, Adelaide

4 February – 28 March 2015

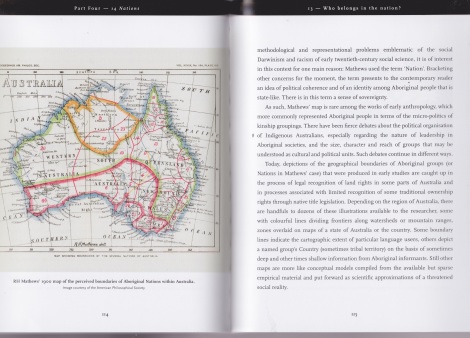

14 Queensland Nations (Nations imagined by RH Matthews) created by Kamilaroi artist Archie Moore was originally developed as an installation for the symposium Courting Blakness at the University of Queensland in 2014 with the intention to disrupt the courtyard space. His flags became a powerful symbol of an anthropologically-imagined nationhood. When transporting this exhibition to Tandanya National Aboriginal Cultural Institute it became something more; it transformed from sign and signifier into the Barthesian concept of mythology to speak back to dominant culture. Freed from the restrictions of flag protocol and storied for visiting gallery groups it evolved into another narrative.

Moore based his flags on the work of self-taught non-Indigenous early 19th century anthropologist RH Matthews who, within his own white privilege and position of knowledge, mapped the boundaries of Indigenous nations within New South Wales and Queensland. Just as the inventor of the Aboriginal flag, Harold Thomas, imagined a flag to unite Aboriginal Australians using recognised symbology, so Archie Moore used the symbols found within the 14 Nations to make flags similar to national flags used across the world. For example we see a constellation of stars in his Kamilaroi flag that represents the Seven Sisters Dreaming, a constellation also recognised by others in the mythology of the Pleiades.

When installing and making use of the flagpoles within the Great Court at the University of Queensland the artworks, now identified as flags, had to follow Government protocol. This action meant that some of the flags could not be flown but it also meant that in having to adhere to the protocols the flags were elevated to recognised symbols of nationalism thus realising the artist’s vision.

When Tandanya curator Troy-Anthony Baylis took delivery of this case of flags he no longer had to follow protocol but could display the work in all its glory. As you entered the space the two largest flags not only made you look up but as you moved into and under the full exhibit you became sheltered under this imagined nationhood. Whether seen through the eyes of gallery visitor at the opening, or while attending the Tandanya Spirit Festival, or within a scholarly visit by university students the flags took on new meanings, freed from flag protocol and Eurocentric dominance. These playful constructions could speak within the language of symbology unfettered, speaking back within the bounds of semiotics, transforming themselves into a mythological knowing as objects imagined; as neither true nor false.

School children sitting patiently listening to a floor talk put their hands up in unison wanting to imagine their own flag designs. University students were challenged to think first of the meaning of ‘nations as imagined communities’ as described in Race and ethnic relations edited by Farida Fozdar, Raelene Wilding, and Mary Hawkins; and then of the hidden language of symbology that transcends mere signification with its fullness of meaning and thus to be carried away – as French Semiologist Roland Barthes described – by myth and to open a dialogue to challenge colonisation and nations imagined by the coloniser. Moore’s work is therefore raised into the possibility of nationhood.

—-

Dr Frances Wyld is a Martu woman, writer and lecturer at Wirltu Yarlu, University of Adelaide.

—-

Eyeline No.82, 2015 – ARCHIE MOORE in conversation with Wes Hill

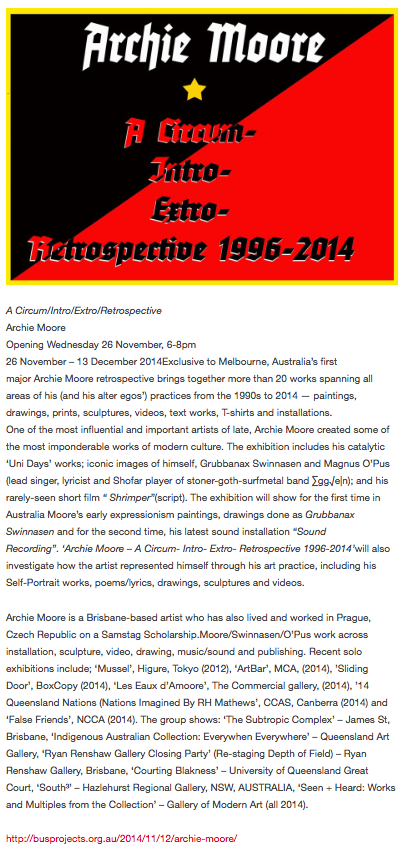

Room Sheet : A Circum/Intro/Extro/Retrospective – Bus Projects Nov-Dec 2014

ARCHIE MOORE’S OLFACTORY ART

By LAURA BANNISTER

“When I said one memory was ‘pencils,’ he had his finger pointed to the ceiling with his eyes and said, ‘Aha! Cedar wood!’ and knew which compounds would achieve this.”

Archie Moore—an Aboriginal, multidisciplinary artist based in Queensland, Australia—is recounting his meetings with Jonathon Midgley of Damask Perfumery, a stranger-turned-collaborator and epicurean of smells. Moore describes Midgley as wizard-like in his olfactory observations, a man who could sniff one’s ‘stuff’ (concepts, memories) and translate them into something fantastically ephemeral: precise and complex aromas that climb up one’s nostrils and move around the brain, somewhere near the limbic system. As the two worked together, Midgley talked like a winemaker: he spoke of base and high notes and detected hints of cherry.

They say an artist is only as good as their last work (who exactly they are, I’ve never been sure). Moore’s last series, “Les Eaux d’Amoore,” is a selection of perfumes exhibited at the Commercial, a modestly sized—but ambitious—gallery in Sydney. In the dimly lit space, tall, clear bottles sat atop glowing shelves, accompanied by stacks of blotting cards—the kind dished out in department stores by women with clean hair and white teeth.

“Technically, they are all eau de toilettes because I didn’t need them to last on your skin,” says Moore. “I was only concerned with the immediate experience of smelling them. It was cheaper to make them this way also.”

Each of the seven smells in “Les Eaux d’Amoore” is a forceful glimpse into another’s memories, a sort of Rorschach test that references, as Bec Dean notes in the exhibition text, scent’s function as “a seat of prejudice.”Investiture smells like the artist’s first girlfriend. She wore rose oil and Elizabeth Arden’s Red Door. Presage is graphite pencils and paper, riddled with anxieties from the first day of school. Un Certain T’y has the odor of Moore’s father, weighty and earthy, reminiscent of clay and wood-fire smoke. Moore explains, “When I was very young he would take me with him to his earthmoving jobs, digging up the earth for dams. The perfume name is me having fun playing with words: uncertainty in the English sense, because I was always unsure if he was my biological father.”

Moore’s youth—marked by poverty, volatility, and the isolation of growing up as an Aboriginal child in a white-dominated environment—felt awkward set against these symbols of wealth and excess: fancy bottles housing perfume compounds, sterile shelving. The intention was to unsettle, of course, creating a deliberate tension between the physical work and Moore’s ideas.

The funny thing about memories is that they are fragile and unreliable, nearly always selective. We rarely remember things as they really occurred, glossing over bits, hyperbolizing. Moore is hyper-aware of this tendency to reconstruct, along with our inability to truly grasp the recollections of another. Much of his work is participatory in this way, initiating a dialogue concerning race and Aboriginal politics, integrating his lived experience and asking others to fill in the blanks. Good art, Moore knows, has a way of embedding itself in an audience, leaving some residue as the viewer walks away.

“I wanted it to be an audience sniffing my memories,” says Moore, “but how can they remember what I remember? Do I even have an accurate recollection of my own experience? I see all this as a bit of a metaphor for the failure of reconciliation. Can indigenous and non-indigenous ever really, fully understand or have empathy for each other?”

As an artist, Moore is easily bored, exploring various formal considerations (drawings, sculpture, videos, installation, photographs) until he pinpoints the one that will best convey an idea. For one self-portrait, a twisted, confrontational readymade, he covered a taxidermy Bull Terrier in shoe polish and attached a collar which read, “Archie.” For another piece, Clover, a tent-like structure propped up with sticks, he interrogated the cruelties of political ignorance and institutional racism. Currently, Moore is designing a flag for every nation of Queensland, based on an anthropological map dating to 1900. “There’s fourteen Aboriginal nations he identified,” Moore says of the map’s creator, “rather inaccurately, I would say, but he was one of the first to see Aboriginal Nationhood.”

Moore graduated from Queensland University of Technology in 1998, with a bachelor of visual arts. Three years later, he was awarded an international scholarship, enabling him to study at Prague’s Academy of Fine Arts. The experience merely extended his sense of psychological displacement to another locale: Moore often feels “like a bubble, floating on an ocean of acquaintances.” Still, he is no stranger to accolades: shortlisted six times for the Telstra National Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Award, and the 2010 winner of the Woollahra Small Sculpture Prize.

Moore used to wear perfume (a synthetic rose oil) but it has long been discontinued. He now goes without one and receives no complaints on his natural scent.

—–

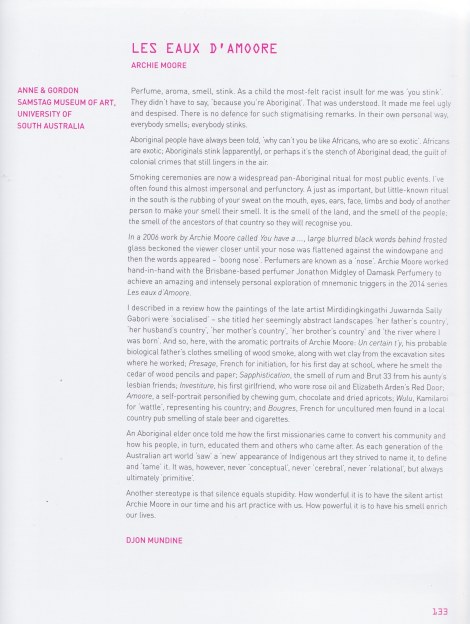

CATALOGUE ESSAY FOR Les Eaux d’Amoore at The Commercial, Sydney 2014

Archie Moore’s diverse practice gives form and presence to the frail substances upon which Australian mainstream culture is built, examining the repercussions of its colonial past and the dispossession of Aboriginal people. He takes materials that we might consider benign and gives them weight and power with language that elicits racial and religious meaning. His new work, Les Eaux d’Amoore, a series of seven portraits in perfume, engages with another kind of fabrication of meaning.

Enfleurage, expression and distillation are perfume extraction techniques that enable a scent to be taken from its origins and be applied to the human body. Ordinarily, through these processes, a flower’s scent can retain vibrancy and aliveness long after its plant origin has died, and in this way traditional perfume manufacture could be described as a kind of plant memorial. Perfume is olfactory representation, a semblance which stands in for the dead original, rather like a photograph of a person. But, unlike photographs which can be stored away and forgotten, scents arrive in our nostrils unbidden, triggering biochemical reactions that can stimulate strong memories, associations and feelings. We can’t shut them out. They assault us.

Moore’s series of seven perfume portraits, which venture considerably beyond the standard repertoire of traditional perfumes, delve deeply into the idea of scent as memory and seat of prejudice. Working with a master perfumer to resynthesise the strongly associative smells of his youth in South-East Queensland, this suite of aromas range from the at-face-value benign but in-fact anxiety-inducing odours of graphite pencils and paper from his first day of school in Presage, to the rather more routinely unpleasant combination of Brut 33 and rum in Sapphistication. For Moore, his concoctions are recipes associated with familial uncertainty, shame, poverty and the brutal slap of everyday racism as experienced by an Aboriginal child growing up in a less than hospitable white dominated society. But how will we interpret them from our own perspectives? Like traditional perfumes, these scents may react strongly against our own skin, inflame our nostrils, cause nausea or force thought to the images they stir. For some they may smell like nothing much at all.

In this work, Moore has crafted olfactory resonances of his past which, when we encounter them, will be absorbed by our bodies whether we want them to be or not. As we bring the scents inside ourselves, can we imagine the memories of the artist that they relate to, or the possibility/impossibility for empathy, understanding or even reconciliation? As with perfume, this transference of smell-memory from origin to host is highly subjective, impossible to grasp or to retain. The scent eventually wears off. And, like memories or personal experiences, Moore asks can we ever really share, know or understand those of another?

Bec Dean

—————

http://panopticpress.org.au/?page_id=1709 – An extended profile, including coverage of Les Eaux d’Amoore at the Commercial – written by Simon Marsh for Panoptic Press.

Who’s Afraid of Indigenous Art?

Similarly we may ask the question, who is afraid of conceptual art? (1) However, when we are met with a combination of both propositions, augmented by a third, then perhaps the more appropriate question to ask, would seemingly be fashioned along the lines of – who is afraid of the relational aesthetics of conceptual Indigenous artist Archie Moore? Perhaps not so surprisingly – in a country infected with social divisiveness, wedge politics, historical revisionism and an oligopolised media – quite a few! Unsparingly, since 1788, on an unprecedented level, Australia has been a country embroiled in an utterly disgraceful story of imperialism, exploitation, overt racism, eugenics and attempted genocide of its Indigenous inhabitants. And yet to this day we witness the neo-liberal insistence through politically motivated, aggressively directed media campaigns, to wrest control of Australia’s past – to win back a glorified white history as a form of political and social resource – through an overt and monotone beige alignment with orchestrated understandings of Anglo-Saxon acts of heroic achievement. (2) Against this pocked landscape of reprehensibility, one could say we are adequately positioned to view the oeuvre of the conceptually consummate artworks of Archie Moore. To be more precise, Moore’s oscillation between the formal qualities inherent in fluxus, seen as the insistence of viewer participation in the completion of an artwork and notions of the dialectical opposition conceptual art set in play with regard to its unremitting institutional critique, amplified by an understanding of Nicolas Bourriaud’s relational aesthetics, amounts to an art that is about art, that is about life. This paradoxical artistic double negative, enlarged by a necessity to reveal the truth of a lived reality, can be seen as the prime mover that drives Moore’s unremitting discourse surrounding contemporary Indigenous identity.

Whilst it remains an accurate observation that conceptual art refuses to be locked down into a defining set of dialectical artistic parameters and in effect remains in opposition to definition, this constant slippage simply does not denote a comprehensive art historical or philosophical knowledge to unravel what at times can be perceived as an indulgent intellectual puzzle. Contrary to popular belief, conceptual art can in fact be experienced in a fairly straightforward manner. Negating the often-held belief that an intellectual rigor is required in approaching conceptualism – similar to a contemporary artistic landscape – it is an art form that entertains open concepts that are allied with an increasingly inflated artistic perimeter. (3) That being said, it remains an advantageous exercise in briefly plotting conceptualism’s lineage and particular idiosyncrasies before aligning Moore’s artwork to this particularly capricious genre.

Emerging in the late 1960s and early 1970s, conceptualism’s pedigree can be retrospectively traced back to Marcel Duchamp’s iconic readymade Fountain 1917. Epitomizing a full frontal assault on convention and good taste the object was refused exhibited status by the Society of Independent Artists. Importantly though, Duchamp’s methodology hinged on the concept of the artist’s choice, the artist’s intervention in the dematerialization of the objects original significance and the re-signification firstly by the title and subsequent perspectival placement within a gallery setting, thereby birthing a revitalized conceptual understanding of the original object as a readymade object of art. (4) Linking the idea of the Duchampian readymade object with the fluxus movement – translated from the Latin meaning flow – originating in 1961, conceived of by George Maciunas – American writer, performance artist and composer – and attracting artistic luminaries such as Yoko Ono and Nam June Paik, a precept of fluxus contained in their 1963 manifesto was to ‘purge the world of bourgeois sickness’, pseudo intellectualism, professionalism and commercial culture. Encompassing ephemera and bordering experimental music, performance, concrete poetics, anti-film, the gesture and actions involved in the artists daily life – often-times requiring spectator participation in the completion of the artwork – fluxus remains an art where anything can substitute for an art work and anyone can and will be encouraged to aid in its production. (5) The assumptions that both of these formal artistic movements addressed, provided a rich vein of semiological practicality for artists to reflect upon and whilst privileging a contemporary hindsight, conceptualism does seem a logical continuation given its lineage of previous artistic endeavor.

The critical discourse currently surrounding conceptual art positions it as an art form that seamlessly dovetails and intermingles with the disciplines of painting, music, video, sculpture, photography, performance and installation art. (6) This trans-disciplinary approach, birthed by Duchamp, toward a fluxus manifestation: a movement that artistically supplemented a contemporary positioning of conceptualism, is clearly evidenced throughout Moore’s work. Spanning the performance of alter egos, video, spoken word, participatory installation, sound art, appropriated texts, an ironic play on meaning and the readymade artistic object, the choices Moore makes are all imbued with his ongoing thesis surrounding implied and overt racial gestures of discrimination and the unceasingly inherent scripting of Indigenous identity by forces that lay outside of Indigeneity. The affront that this attempted rewriting of Indigenous identity sets in play and the highly structured political dynamic of a social participation was clearly evidenced throughout the opening of Chalk it Out at the Queensland art gallery. The workshop come participatory performative installation by Moore consisted essentially of a blackboard that the spectator was invited to mark with white chalk. Whilst primarily a fluxus inspired intervention incorporating a purity of relational aesthetics, the finished object powerfully and conceptually cuts to the heart of what it is that Moore continually and accurately articulates: the writing over of a seemingly invisible originating ‘Other’ with the defining text – the established set of attitudes – that lend meaning and context to the destabilization of a sovereign nation and the uninterrupted abject reality caused by the brutal invasion of an unjust imperialist force.

The concept of an authentic white Australian memory as one suffused with an inherent underlying prejudice, creates a palpable tension throughout Moore’s work. This constructed tension existing between the object and the idea, whilst designed to implicate the spectator as performing a defining role in the misdirected arrogance of assimilationist ideology can also be positioned as a doorway being opened to a constructive dialogue. However the seeming inadequacy of the concept underlining the word ‘sorry’, the complicity of silence and the inactivity beyond an initial thought seems to be close at hand. Moore simply excels at conceptually constructing and exploring an ironic fabricated ‘truth’. Whether this ‘truth’ is exposed through the use of seemingly benign nursery rhymes, the language of the racist cliché or the schoolyard taunt as expressly witnessed in the exhibition Depth of Field (2006), or is rationally questioned through the use of religious iconography and scripture as seen in 10 Missions from God (2012), or indeed revealed by the mark of the spectator as exposed by Chalk it Out, it is an irony shaded with bitterness, anger, extreme sarcasm and perhaps most importantly, knowledge: a knowledge that has become artistically astute in the dismantling of the fabricated veneer of a white ‘truth’.

Whilst it is commonly debated throughout certain circles that the medium of conceptual art is the idea and as the reasoning runs, the idea of conceptualism is not bound by the spatio-temporality of the physical object. This line of reasoning however negates the many instances seen throughout conceptualism where the physical artistic object clearly insists its integral relationship to the work as a whole. The privileging of the idea alone as the medium and traditionally therefore that which mediates our overall aesthetic appreciation is simply not true. (7) In the case of the readymade, viewed as beginning its life as an artistically insecure object, as soon as that re-contextualized object crosses the threshold of institutional acknowledgment, both the object and its idea accumulate artistic status and can be seen to be operating in tandem in the construction of a medium. A case in point, to highlight the oscillation between the object and idea in formulating aesthetic appreciation is Moore’s Black Dog (2013).

Shortlisted for the University of Queensland Art Museum’s Self-Portrait Prize and subsequently acquired by the National Gallery of Australia, Black Dog epitomises the co-joined status of both the object and the idea in formulating a medium. Contemporary audiences – reads the curatorial didactic – are fundamentally prepared – through the advent of varying media – to devour a diversity of articulated forms of a more personal nature. Significantly Moore’s entry consisted of a taxidermied Bull Terrier, colloquially, better known as a Pig Dog. Hand colored black and wearing a tanned collar with the nametag “Archie” attached, it assumed pride of place sitting on a plinth in the central gallery with a decidedly perplexed and quizzical look on it’s face. The initial shock, on the sensible ideal of self, of viewing Black Dog in an institutional surround is arguably seen as the object initiating an aesthetic intervention. Following this initial corruption of the sensible, the conceptual idea’s attached to the readymade object simply compound this aesthetic experience and together act – via a process of oscillation between the two – in the elongation of a decidedly metaphysical moment. Of particular importance here is that Black Dog highlights the ways in which conceptual art can effectively operate in a fairly straightforward manner. Seen as a threat and potentially dangerous and whilst surrounding the universality of throwaway racist commentary inflicted on a marginalised people, the “resurrected” self-portrait conceptually implicates the spectator within this dynamic and asks us to consider the validity of an ongoing perpetration of this conspicuous discrimination. The conceptual teasers radiating from Moore’s project are metaphysically far greater than that of the institutional space that houses them. We are conceptually invited to co-habit Moore’s skin and together traverse the 226 years (to date) of the consequence of Indigenous dispossession.

The highly refined nature of Moore’s conceptual irony holds a distinct capacity to open onto a liminal space of uncertainty before it’s simply too late to retreat to a perceived space of comfort. This refinement of uncertainty, of meaning, is highlighted in Moore’s most recent exhibition Les Eaux D’Amoore (2014). Running from June 13 through to July 12, 2014 and showing at The Commercial Gallery Redfern, Les Eaux D’Amoore investigates associations between a lived, extreme poverty, the unpredictability of familial relations, remorse and a lived sense of self as triggered by an olfactory recall. Working closely with master perfumer Jonathon Midgley of Damask Perfumery, the artist’s series of seven perfume portraits, reminiscent of the anxieties experienced throughout childhood is simply a formidable display of Moore’s continually maturing artistic range. Comparable to an exclusive high-end department store display, the exhibition riffs off a commercial culture, specifically, the up-market clinical aesthetic of stainless steel fixtures, light-boxes, glass, sterility, perfumed compounds and fragrance blotter cards, all, traditionally the purview of a deluxe personal adornment marketed by couturiers operating under a presumed superior aesthetic of mystique. This schism of realities becomes Moore’s paradoxical premise that drives an investigation surrounding the reality of a remembered comprehension an empathetic understanding of an otherwise fleeting ethereal ‘Other’. Yet again Moore reaches back to the general principles of fluxus in fine-tuning the inclusive truth of his conceptual practice. The overall structure of Les Eaux D’Amoore invites a participatory performance by the spectator to complete the artwork. The choice of the spectator revolves around which perfume to wear – Investiture, Un Certain T’y, Wulu, Saphistication or Amoore – revolves around which scent of Moore’s remembered past to test and adorn themselves with, if any, in an explicit gesture of alignment, in the ultimately unverifiable spirit of empathy, understanding, hope, trust and reconciliation.

Aligned with the Kamilaroi language group, Archie Moore graduated with a Bachelor of Arts Visual Arts from The Queensland University of Technology in 1998. In 2001 he was the recipient of The Millennial Anne and Gordon Samstag International Arts Award augmenting his Batchelor of Arts with a year of non-degree study at the Academy of Fine Arts Prague. Living and working in Australia Archie has exhibited extensively both throughout Australia and Internationally. Notably, he has been shortlisted numerous times for the Telstra National Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Award and has exhibited in Shanghai, Paris, Japan, Belgium and San Francisco. Whilst his works inhabit many private collections of note his art has been acquired into the collections of the Gallery of Modern Art, Brisbane and the National Gallery of Australia. Archie Moore is currently represented by The Commercial Gallery Sydney.

Published 13 June, 2014. Simon Marsh view profile.

Visit Archie Moore’s website…here.

Currently exhibiting Les Eaux D’Amoore: current through 12-07-2014.

The Commercial Gallery 148 Abercrombie Street Redfern PO Box 830 Strawberry Hills NSW, Australia, 2012 T: +61 2 8096 32 92 | M: +61 414 295 994 Skype: the.commercial Wednesday – Saturday 11am to 6pm (or by appointment)

http://www.thecommercialgallery.com

1. Goldie, Peter and Schellekens, Elisabeth. Who’s Afraid of Conceptual Art? Routledge. 2010.

2. Macintyre, Stuart. The History Wars. Sydney Papers, 09 September, 2003. Vol. 15, Issue 3/4.

3. Above n1.

4. ‘The Richard Mutt Case’, The Blind Man, New York, no 2, May 1917.

5. Corris, Michael. Grove Art Online. Oxford University Press, 2009.

6. Above n1.

Recommended: Art & Language. Voices Off: Reflections on Conceptual Art. Critical Inquiry, Vol. 33, No. 1 (Autumn 2006), pp. 113-135. The University of Chicago Press.

[Eyeline 52 autumn winter 2003]

[Eyeline 52 autumn winter 2003]

[Vault: New Art & Culture – Issue 3, April 2013, pages 32 & 33] ‘Light from Light’ exhibition publication p 34-35, MAAP – Media Art Asia Pacific

‘Light from Light’ exhibition publication p 34-35, MAAP – Media Art Asia Pacific